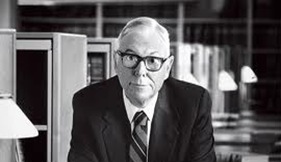

Charlie Munger is the 86 year old partner of Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway. He is the lesser known of the dynamic duo, but Munger has had a significant, almost unquantifiable impact on the way Warren Buffett thinks and on the fortunes of the Berkshire shareholders. The reason for this impact is that, In addition to being a great investor, he is an extraordinary thinker.

Charlie Munger is the 86 year old partner of Warren Buffett at Berkshire Hathaway. He is the lesser known of the dynamic duo, but Munger has had a significant, almost unquantifiable impact on the way Warren Buffett thinks and on the fortunes of the Berkshire shareholders. The reason for this impact is that, In addition to being a great investor, he is an extraordinary thinker.

Peter Kaufman has put together all his talks, lectures, and public commentary over the years into one of my favorite book: “Poor Charlie’s Almanack: The Wit and Wisdom of Charlie Munger.” If I had to name a book that has changed the way I think, it has to be this book. Even though every chapter in this book is worth its weight in gold, in this post, I will quote excerpts from one talk that I really like – the USC Gould School of Law Commencement Address at University of Southern California on May 13, 2007.

“I’ve scratched out a few notes, and I’m going to try and give an account of certain ideas and attitudes that have worked well for me. I don’t claim that they’re perfect for everybody. But I think many of them contain certain universal values and that many of them are ‘can’t fail’ ideas.

What are the core ideas that helped me? Well, luckily I had the idea at a very early age that the safest way to try to get what you want is to try to deserve what you want. It’s such a simple idea. It’s the golden rule. You want to deliver to the world what you would buy if you were on the other end. By and large, the people who’ve had this ethos win in life, and they don’t just win money and honors. They win the respect, the deserved trust of the people they deal with. And there is huge pleasure in life to be obtained from getting deserved trust.

Another idea, and this may remind you of Confucius, is that the acquisition of wisdom is a moral duty. It’s not something you do just to advance in life. And there’s a corollary to that idea that is very important. It requires that you’re hooked on lifetime learning. Without lifetime learning, you people are not going to do very well. You are not going to get very far in life based on what you already know. You’re going to advance in life by what you learn after you leave here. I constantly see people rise in life who are not the smartest, sometimes not even the most diligent. But they are learning machines. They go to bed every night a little wiser than they were that morning. And boy, does that help, particularly when you have a long run ahead of you. Consider Warren Buffett. If you watched him with a time clock, you’d find that about half of his waking time is spent reading. Viewed up close, Warren looks quite academic as he achieves worldly success.

Another idea that was hugely useful to me was one of learning all the big ideas in all the big disciplines. And because the really big ideas carry about 95% of the freight, it wasn’t at al hard for me to pick up about 95% of what I needed from all the disciplines and to include use of this knowledge as a standard part of my mental routines. Once you have the ideas, of course, you must continuously practice their  use. Like a concert pianist, if you don’t practice you can’t perform well. So I went through life constantly practicing a multi-disciplinary approach. It doesn’t help you much just to know something well enough so that on one occasion you can prattle your way to an A in an exam. You have to learn many things in such a way that they’re in a mental latticework in your head and you automatically use them the rest of your life. If many of you try that, I solemnly promise that one day most will correctly come to think, ‘Somehow I’ve become one of the most effective people in my whole age cohort.’ And, in contrast, if no effort is made toward such a multi-disciplinarity, many of the brightest of you who choose this course will live in the middle ranks, or the shallows.

use. Like a concert pianist, if you don’t practice you can’t perform well. So I went through life constantly practicing a multi-disciplinary approach. It doesn’t help you much just to know something well enough so that on one occasion you can prattle your way to an A in an exam. You have to learn many things in such a way that they’re in a mental latticework in your head and you automatically use them the rest of your life. If many of you try that, I solemnly promise that one day most will correctly come to think, ‘Somehow I’ve become one of the most effective people in my whole age cohort.’ And, in contrast, if no effort is made toward such a multi-disciplinarity, many of the brightest of you who choose this course will live in the middle ranks, or the shallows.

Another idea that I discovered is encapsulated by the story about the rustic who ‘wanted to know where he was going to die, so he wouldn’t go there.’ The rustic who had that ridiculous sounding idea had a profound truth in his possession. The way complex adaptive systems work, and the way mental constructs work, problems frequently become easier to solve through ‘inversion.’ If you turn problems around into reverse, you often think better. Those who have mastered algebra know that inversion will often and easily solve problems that otherwise resist solutions. And in life, just as in algebra, inversion will help you solve problems that you can’t otherwise handle.

Let me use a little inversion now. What will really fail you in life? What do we want to avoid? Some answers are easy. For example, sloth and unreliability will fail. If you’re unreliable it doesn’t matter what your virtues are, you’re going to crater immediately. So, faithfully doing what you’re engaged to do should be an automatic part of your conduct. Of course, you should avoid sloth and unreliability.

Another thing to avoid is extreme intense ideology, because it cabbages up one’s mind. If you’re young, it’s particularly easy to drift into intense and foolish political ideology and never get out. When you announce that you’re loyal member of some cult-like group and you start shouting out the ideology, what you’re doing is pounding it in, pounding it in, pounding it in. You’re ruining your mind, sometimes with startling speed. So you want to be very careful with intense ideology. It presents a big danger for the only mind you’re ever going to have. I have what I called the ‘iron prescription’ that helps me keep sane when I drift toward preferring one intense ideology over another. I feel that I’m not entitled to have an opinion unless I can state arguments against my position better than the people who are in opposition. I think I am qualified to speak only when I’ve reached that state. That probably is too rough for most people, although I hope it won’t ever become too tough for me. This business of not drifting into extreme ideology is very, very important in life. If you want to end up wise, heavy ideology is very likely to prevent that outcome.

Another thing to avoid is extreme intense ideology, because it cabbages up one’s mind. If you’re young, it’s particularly easy to drift into intense and foolish political ideology and never get out. When you announce that you’re loyal member of some cult-like group and you start shouting out the ideology, what you’re doing is pounding it in, pounding it in, pounding it in. You’re ruining your mind, sometimes with startling speed. So you want to be very careful with intense ideology. It presents a big danger for the only mind you’re ever going to have. I have what I called the ‘iron prescription’ that helps me keep sane when I drift toward preferring one intense ideology over another. I feel that I’m not entitled to have an opinion unless I can state arguments against my position better than the people who are in opposition. I think I am qualified to speak only when I’ve reached that state. That probably is too rough for most people, although I hope it won’t ever become too tough for me. This business of not drifting into extreme ideology is very, very important in life. If you want to end up wise, heavy ideology is very likely to prevent that outcome.

Another thing that often causes folly and ruin is the ‘self-serving bias,’ often subconscious, to which we’re all subject. You think that ‘the true little me’ is entitled to do what it wants to do. For instance, why shouldn’t the true little me get what it wants by overspending its income? Even though, you have to get self-serving bias out of your mental routines, you have to allow for the self-serving bias of everybody else, because most people are not going to be very successful at removing such bias, the human condition being what it is. If you don’t allow self-serving bias in the conduct of others, you are, again, a fool.

I watched the brilliant and worthy Harvard Law Review-trained general counsel of Solomon Brothers lose his career there. When the able CEO was told that an underlying had done something wrong, the general counsel said, “Gee, we don’t have any legal duty to report this, but I think it’s what we should do. It’s our moral duty.” The general counsel was technically and morally correct. But his approach did not persuade. He recommended a very unpleasant thing for the busy CEO to do and the CEO, quite understandably, put the issue off, and put it off, and not with any intent to do wrong. In due course, when powerful regulators resented not having been promptly informed, down went the CEO and the general counsel with him. The correct persuasive technique in situation like that was given by Ben Franklin.

He said, “If you persuade, appeal to interest, not to reason.” The self-serving bias of man is extreme and should have been used in attaining the correct outcome. So the general counsel should have said, “Look, this is likely to erupt into something that will destroy you, take away your money, take away your status, grossly impair your reputation. My recommendation will prevent a likely disaster from which you can’t recover.” That approach would have worked. You should often appeal to interest, not to reason, even when your motives are lofty.

Perverse associations are also to be avoided. You particularly want to avoid directly working under somebody you don’t admire and don’t want to be like. It’s dangerous. We’re all subject to control to some extent by authority figures, particularly authority figures who are rewarding us. Dealing properly with this danger requires both some talent and will. I coped in my time by identifying people I admired and by maneuvering, mostly, without criticizing anybody, so that I was usually working under the right sort of people. Generally, your outcome in life will be more satisfactory, if you work under people you correctly admire.

Perverse associations are also to be avoided. You particularly want to avoid directly working under somebody you don’t admire and don’t want to be like. It’s dangerous. We’re all subject to control to some extent by authority figures, particularly authority figures who are rewarding us. Dealing properly with this danger requires both some talent and will. I coped in my time by identifying people I admired and by maneuvering, mostly, without criticizing anybody, so that I was usually working under the right sort of people. Generally, your outcome in life will be more satisfactory, if you work under people you correctly admire.

Engaging in routines that allow you to maintain objectivity are, of course, very helpful to cognition. We all remember that Darwin paid special attention to disconfirming evidence, particularly when it disconfirmed something he believed and loved. Routines like that are required if a life is to maximize correct thinking.

Engaging in routines that allow you to maintain objectivity are, of course, very helpful to cognition. We all remember that Darwin paid special attention to disconfirming evidence, particularly when it disconfirmed something he believed and loved. Routines like that are required if a life is to maximize correct thinking.

I frequently tell the apocryphal story about how Max Planck, after he won the Noble Prize, went around Germany giving a same standard lecture on the new quantum mechanics. Over time, his chauffeur memorized the lecture and said, “Would you mind, Professor Planck, because it’s so boring to stay in our routine, if I gave the lecture in Munich and you just sat in front wearing my chauffer’s hat?” Planck said, “Why not?” Ant the chauffeur got up and gave this long lecture on quantum mechanics. After which a physics professor stood up and asked a perfectly ghastly question. The speaker said, “Well, I’m surprised that in an advanced city like Munich I get such an elementary question. I’m going to ask my chauffeur to reply.” Well, the reason I tell that story is not celebrate the quick wittedness of the protagonist. In this world I think we have two kinds of knowledge. One in Planck knowledge, that of the people who really know. They’ve paid the dues, they have the aptitude.

I frequently tell the apocryphal story about how Max Planck, after he won the Noble Prize, went around Germany giving a same standard lecture on the new quantum mechanics. Over time, his chauffeur memorized the lecture and said, “Would you mind, Professor Planck, because it’s so boring to stay in our routine, if I gave the lecture in Munich and you just sat in front wearing my chauffer’s hat?” Planck said, “Why not?” Ant the chauffeur got up and gave this long lecture on quantum mechanics. After which a physics professor stood up and asked a perfectly ghastly question. The speaker said, “Well, I’m surprised that in an advanced city like Munich I get such an elementary question. I’m going to ask my chauffeur to reply.” Well, the reason I tell that story is not celebrate the quick wittedness of the protagonist. In this world I think we have two kinds of knowledge. One in Planck knowledge, that of the people who really know. They’ve paid the dues, they have the aptitude.  Then we’ve got the chauffeur knowledge. They have learned to prattle the talk. They may have a big head of hair. They often have a fine timbre in their voices. They make a big impression. But in the end what they’ve got is chauffeur knowledge masquerading real knowledge. You’re going to have the problem in your life of getting as much responsibility as you can into the people with the Planck knowledge and away from the people who have the chauffeur knowledge. And there are huge forces working against you.

Then we’ve got the chauffeur knowledge. They have learned to prattle the talk. They may have a big head of hair. They often have a fine timbre in their voices. They make a big impression. But in the end what they’ve got is chauffeur knowledge masquerading real knowledge. You’re going to have the problem in your life of getting as much responsibility as you can into the people with the Planck knowledge and away from the people who have the chauffeur knowledge. And there are huge forces working against you.

Another thing that I have found is that intense interest in any subject is indispensable if you’re really going to excel in it. I could force myself to be fairly good in a lot of things, but I couldn’t excel in anything in which I don’t have an intense interest. So to some extent you’re going to have to do as I did. If at all feasible, you want to maneuver yourself into doing something in which you have an intense interest.

The last thing that I want to give to you, as you go out into a profession that frequently puts a lot of procedure and some mumbo jumbo into what it does, is that complex bureaucratic procedure does not represent the highest form civilization can reach. One higher form is a seamless, non-bureaucratic web of deserved trust. Not much fancy procedure, just totally reliable people correctly trusting one another. That’s the way an operating room works at the Mayo Clinic. If lawyers would there introduce a lot of lawyer-like process, more patients would die. In your own life what you want to maximize is a seamless web of deserved trust. And if your proposed marriage contract has 47 pages, my suggestion is that you not enter.”